|

|

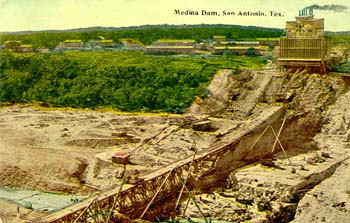

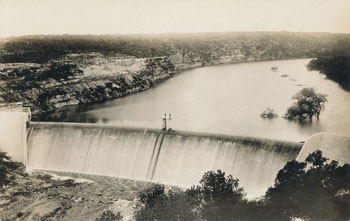

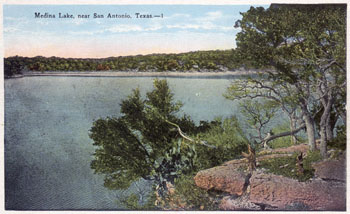

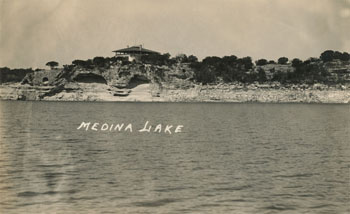

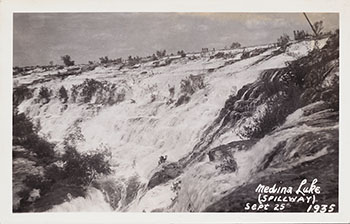

Medina Lake and Canal System Medina Lake was constructed between 1911-1912 as an irrigation reservoir. An extensive canal system delivers water to 34,000 acres of blackland prairie farmlands below the Balcones escarpment around Castroville, La Coste, Natalia, and Devine. Portions of the canal extend to urban San Antonio, just outside Loop 1604. At the time it was constructed, it was the biggest irrigation project west of the Mississippi. At spillway capacity, Medina Lake covers about 5,575 acres, has a length of 18 miles, a maximum width of three miles, 110 miles of shoreline, and a storage capacity of 254,823 acre-feet. In addition to the main dam, there is a smaller dam about four miles downstream that creates Diversion Lake, from which discharges are made to the canal system.

Medina Dam, Medina Lake, and Diversion Lake were constructed partially on the Edwards limestone outcrop, and it has always been assumed the lakes contribute large amounts of water to Aquifer recharge. Seepage losses from Medina Lake and Diversion Lake have been documented by the USGS and other sources since completion of the irrigation structures in 1912. All of the water lost from the lakes has been assumed to enter the Edwards Aquifer, either directly or indirectly through the Trinity Aquifer. In 2004, the United States Geological Survey completed a water budget analysis and concluded that an average of about 3,083 acre-feet recharges each month (Slattery and Miller, 2004). In 2024, the United States Geological Survey completed another study intended to refine previously derived relationships between the elevation of the water surface of Medina Lake and recharge to the Edwards Aquifer and the upper zone of the Trinity Aquifer in the form of seepage losses from Medina Lake and Diversion Lake. As before, it was assumed that losses represent recharge to the Edwards Aquifer and the upper zone of the Trinity Aquifer. Of several methods used, a Weighted Least Squares (WLS) regression equation provided the most accurate accounting, and it suggested that between March 2017 and September 2022, estimated recharge was 224,301 acre-feet. (Slattery, Choi, and Clark, 2024). This would be an average of 3,348 acre-feet per month, which is similar to the conclusion in the 2004 study. However, not all scientists are in agreement that water lost from Medina Lake can be assumed to end up as Edwards recharge. in July of 2016 noted Aquifer scientist Ron Green presented results of a three year study that found water lost from Medina Lake is conveyed downstream by gravels and does not become Edwards recharge. In a presentation to the Bandera County River Authority and Groundwater District, he said "Loss of water of Medina Lake isn’t water that infiltrates down to the Edwards. It’s water that goes out those gravels." He noted "This work provided the basis for a redefinition of the relationship between Medina Lake and Diversion Lake’s system and the Edwards Aquifer." In June of 2021 officials with Texas Parks and Wildlife announced that Medina Lake is one of several in South Central Texas that is infested by invasive zebra mussels, which are native to Eurasia and are harmful to American aquatic ecosystems. They reproduce in huge numbers and can out-compete other native filter feeders, starving them. They can also damage boats, clog water intakes, and litter shorelines with sharp shells that impact recreation. A Brief Historical Sketch

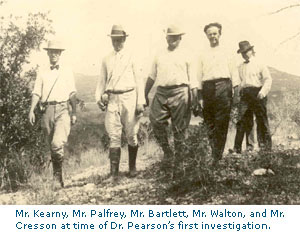

Although Dr. Pearson usually gets credit for building Medina Dam, it was not his idea, and several others were instrumental in the project. According to Rev. Cyril Kuehne, who published a historical account of the dam's construction in 1966 called Ripples From Medina Lake, the original dreamer was Castroville founder Henri Castro. The year was around 1850, and means were not available, but Castro assured his fellow pioneers that someday a great dam would be build to harness the Medina River's floodwaters and irrigate the land around Castroville. For decades, pioneers referred to the area that would become Medina Lake as the "Box Canyon". In 1894, Alex Y. Walton was on a hunting trip to the Box Canyon and, upon inspection of the natural contours, became convinced that waters could be held in readiness here and "according to the need for the service of man." He sought expert advice, and obtained enthusiastic support from engineers Terrell Bartlett and Willis Ranney. After completing surveys and engineering plans, they enlisted the help of Judge Duval West to prepare all the legal papers that would be required.

The pace of construction was frenetic, mostly because the builders expected large floods in the summer of 1913 that would fill the reservoir. The floods never materialized, and after construction was complete in November 1912, it was 18 months before any significant rains occurred. The Lake was not filled to capacity for the first time until September 1919. Wildly fluctuating levels have characterized Medina Lake throughout its entire history, because the Medina River watershed is simply not large enough, and rainfall is not reliable enough, to keep the Lake consistently filled. The designers were likely aware of this. In addition to capturing water from the Medina watershed, in 1911 they had also applied for a diversion of water from the upper Guadalupe River watershed. It would have involved a nine mile flume or tunnel to deliver Guadalupe River water to Mason Creek, and thence into Medina Lake. In 1914 the Board of the Medina Irrigation Company voted to abandon their application for water from the Guadalupe. Even these plans, if they had been completed, might not have ensured that water would always be in Medina Lake, because when the Medina River watershed is dry, flows in the upper Guadalupe can also be very small. Medina Dam was only one component of Alex Walton's comprehensive master plan to establish town sites and sell land to prospective farmers. His group established the Medina Irrigation Company and laid out the town of Natalia, named after Pearson's daughter Natalie. But before land sales could be started, world events spelled financial disaster for the project. When England became involved in World War I in 1914, Pearson's access to British capital was limited, and the Company was placed in receivership. In order to make a personal appeal to British investors for more capital, Pearson and his wife boarded the Lusitania and perished when the ocean liner was torpedoed and sunk by a German submarine on May 7, 1915. After that, U.S. federal courts did not allow any land sales, so the Company leased land until it was released from receivership. The stockholders preferred selling the Company to reorganizing, and there were several failed attempts to keep the endeavor alive, but all the subsequent corporations also went into receivership. Finally, in 1950, assets that had cost $6 million to build were sold for $10 and "other valuable considerations" to the Bexar-Medina-Atascosa Counties Water Improvement District No. 1 (BMA), which voters had established in 1925 to oversee the project. The BMA has continued to own and manage the project ever since.

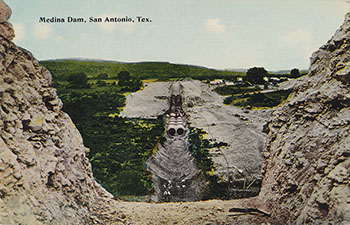

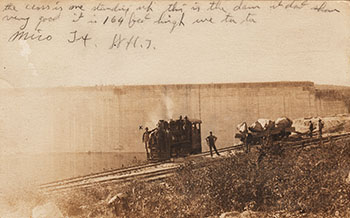

I have reason to believe the photo above came from the personal effects of Alex Walton. I purchased it along with some other photos that were attributed to him by his daughter.

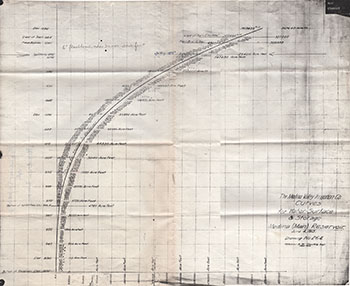

Note: (For a full account of the project's early history and construction, you can obtain a 1999 re-print of Kuehne's book from the Castro Colonies Heritage Association. Medina Lake Storage The graph below estimates the contents of Medina Lake since it was first received significant inflow in 1914. This graph confirms that predicting the past is just as difficult as predicting the future. Estimating the contents of a reservoir always involves uncertainty, and the numbers represented here are not gospel. There is uncertainty in the older numbers, and the newer numbers may change as new information becomes available.

Figuring out how much water is in a lake is accomplished by first conducting a detailed topographic survey of the lake bed and then drawing a relationship between different elevations of the water level, how much surface area the lake covers at each elevation, and how much water it holds. This “Area-Capacity Curve”, as it is called, changes over time because lakes fill in with sediment. When a new topographic survey is conducted, historical data is sometimes adjusted to reflect the new curve, but it is not really possible to know how much of the historical data should be changed. And so we are left with uncertainty. In the case of Medina Lake, there is additional uncertainty because there are several stories about how much water the lake held when it was built, and there was a known error in the measurement of the dam height that affected the reported lake contents for many decades. A brass marker on the dam reports the elevation to be 7.81 feet higher than it actually is. When this was discovered in the 1960s, previous data had to be adjusted, and there is still oftentimes confusion about whether elevations are reported in the “Medina Datum” or in the National Geodetic Vertical Datum (NGVD) of 1929, which is a national standard for establishing vertical controls in surveys. Regarding Lake capacity, a 1994 Surface Water Supply Study by Michael Sullivan and Associates reported the original capacity of Medina Lake was estimated to be 274,000 acre-feet. Sullivan reported that sedimentation surveys performed in 1925, 1937, and 1948 showed the reservoir had an average depletion in storage from siltation of 0.09 percent per year. Using this storage depletion rate, the 1992 capacity was estimated to be about 254,000 acre-feet (Sullivan and Associates, 1994). In 1995, a new volumetric survey conducted by the Texas Water Development Board reported that based on a survey made prior to 1912, the original capacity was 254,000 acre-feet, or 20,000 acre-feet less than reported by Sullivan a year earlier. After analyzing detailed topographic data, the 1995 study concluded the capacity was 254,843 acre-feet (Sullivan, et. al., 1995). So the study results showed no loss of storage in the 84 years since the lake was completed, and actually a slight increase. It is extremely unlikely that could be true. (By the way the two Sullivans in the 1994 and 1995 reports are not the same person). This is the reason I started the storage capacity curve, the red line in the chart above, at 274,000 af - I'm not really believing there was no loss of storage in 84 years. Applying Sullivan's depletion rate of 0.09 percent per year actually works to get exactly to the TWDB 1995 estimate of 254,843 in July of 1994. So the curve declines at Sullivan's rate until that time. This leaves the question of why there are times, such as in the 1930s and early 1960s, when the Lake appears to be very full and was probably discharging over the spillway, but still does not appear to be at capacity. Again - uncertainty. Perhaps the 274,000 really was an overestimate, or perhaps the storage volumes for those times were underestimated. Another possibility is that flash boards once mounted on the spillway served to increase the storage capacity. An Area-Capacity curve prepared for the Medina Valley Irrigation Company on June 4, 1913 showed the capacity at the spillway elevation was 254,010 af, but there is a handwritten note that says "six foot flashboard adds 30,000 acre-feet." In any case, the figure of 254,843 acre-feet has been used since 1995 as the official Lake volume. If that was accurate in 1995, we know it can’t be correct today. Since 1995 there have been several major floods and drastic inflows of silt. An unofficial measurement of the silt level made by USGS workers in November of 2012 suggested that near the dam, the silt layer is 13 feet higher than the lowest water level recorded in 1948. In other words, the capacity of the Lake has obviously been reduced, but no one knows by how much. With all of that said, let me add my additional caveats about the data used in the charts. First of all, there is no single authoritative source, I cobbled it together from several places. In years past, the USGS published data through 1989 that is no longer considered reliable enough to appear on their website. Their current data set starts in 1997. I used the historical USGS data anyway, as reported in a table from Sullivan’s 1994 Water Supply Study. For December 1990 to January 2012, I used data I got from the Texas Water Development Board in a public information request. For data after January 2012, I calculated the month-end volume using the average of 15-minute values reported on the last day of the month by the USGS National Water Information System. The TWDB and the USGS generally agree on the latest numbers, as TWDB gets it from the USGS gage. There is no official source for 1990 data from January to November – the Texas Water Development Board reports it as ‘missing.’ I derived the numbers from fishing reports published in the San Antonio Express-News on the first Thursday of every month. I consider this reliable data, as fishermen never lie. I calculated the amount of water in the Lake using the output of the 1995 volumetric survey and how many “feet down” the Lake was reported to be. The results fit right into the missing slot very nicely and actually seem very plausible, given the rainfall pattern that occurred in 1990. Below is a graph that shows estimated storage volume as a percentage of capacity since 1991. Generous rains fell over the region in 2012, but none of it fell above Medina Lake, so the Lake continued to drop and finished 2013 at less than 4% of capacity. Rains in May and June of 2014 were above average, but they had little effect on the Lake. Rains that have little effect on the Lake may reflect a new normal. In recent years, large areas of the Hill Country are becoming gentrified, with large ranches cut up into small residential ranchettes. Each new resident drills a new well, and many of them construct impoundments on tributaries of the Medina River to create private lakes. All of this appears to be impacting the volume of water that ends up in Medina Lake during smaller rainfall events. In May of 2015, tremendous rains overwhelmed any of these new factors affecting inflow and the Lake gained almost 40% of its capacity in just one day, on May 24. It finished the month at 53% full. In June of 2015, the BMA resumed deliveries of water to irrigators, and the Lake was stocked with 204,000 baby bass. By the end of June, it had recovered to almost 75% full, and it finished 2015 at just under 64% full. In May of 2016, more than nine inches of rain over the region brought the Lake to full capacity for the first time since September of 2007. By December of 2020, it had fallen to less than half full and by late 2024 was less than 3% full. The Lake started 2025 at about 2.5% full.

Early Tourism to Medina Lake

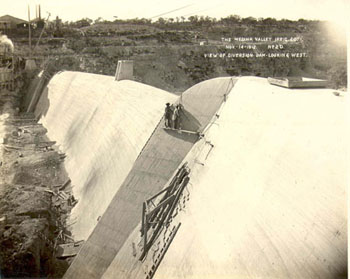

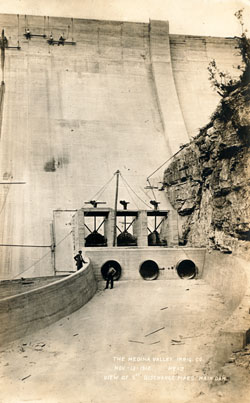

Diversion Dam in The Masked Rider, 1919 In the 1919 silent film classic(?) The Masked Rider, villainous Pancho (Paul Panzer), is so fed up with Texan ranchers on the other side of the border that he hatches a plot to blow the dam and drown everybody for miles around. A damsel that Pancho has taken captive (Ruth Stonehouse) gets a note to Texas Rangers in time for them to ride and try to save the day. A gunfight ensues, with lots of dangerous stunts on the dam. One of the lawmen being shot at is Lon Hildebrandt, an actual Texas Ranger. The scene is shot on Diversion Dam, not Medina Dam, so blowing it would not have drained Medina Lake. Maybe villains are just kinda stupid, or maybe the producers saw that Diversion Dam was more visually striking and offered more opportunity for adventurous frontier escapades. For dam enthusiasts, the interesting part is a look at how the gates were operated manually to release water to the canal system. I stole this video from The Serial Channel on youtube. The video restoration was done by Eric Stedman, with music by Kevin MacLeod and screams by Wilhelm.

Medina Lake: Waters of Controversy Who owns and uses Medina Lake water and the land around the Lake has been a nagging source of concern for local landowners. Many issues were brought to a head during the droughts of '96 and '98, and long-standing tensions between the BMA and local landowners escalated. The function of the BMA is to provide irrigation water to farmers downstream, and storing this irrigation water has been the purpose of the Lake since it was built. The Lake failed completely three times before 1960, but in the wet decades of the 1960s and 70s many people purchased or built homes adjacent to Medina Lake believing they owned lakefront property and that a Lake would always be there. A large residential and recreational economy grew up around the use of Medina Lake water. During the 96-98 drought years, many became concerned about low Lake levels and were shocked to learn that their property boundaries were in dispute, they were unable to restrict access by non-landowners to the Lake, they had no ownership of water, and they had absolutely no guarantee there will be any water in Medina Lake. The recreational economy and property values were impacted by consistently low Lake levels, and drinking water wells of lakeside property owners were also affected. The property boundary dispute involves who owns a strip of land between the elevations of 1072' and 1084' feet above sea level known as the 'Contour Zone'. The top of Medina Dam is at 1084', while the top of the spillway is at 1072'. The BMA claims it owns almost all the land below the 1084' line, while local landowners claimed the BMA only has the right to flood the land. Many landowners built improvements or septic tanks in the Contour Zone, which they insist they are allowed to do "at their own peril". Since there is 12' feet of elevation between the tops of the spillway and the Dam, there is always a strip of land encompassing at least 12' in elevation between the Lake level and the BMA-claimed property line. Low Lake levels often expose a much larger strip of land adjacent to the Lake that offers enticing party spots. So to make matters worse, people who own land adjacent to the Contour Zone often come home to find large boisterous parties happening in front of their homes. Many were in favor of having access to the land below 1084' restricted or eliminated. The controversy about who is allowed to use Medina Lake also involves people who own land in the surrounding hills. For decades the BMA has had an "open Lake" policy. And policy aside, many in the hills nearby have deeds that contain language they claim allows them to use the waters for fishing and swimming. There are hundreds of roads that are used to access the Lake; most are on easements and BMA property, but some cross private property. Many who own land adjacent to the "ten eighty four line" argue that since they pay much higher taxes, they should have exclusive use of the waterfront and use by those in the hills should be restricted or eliminated. People in the hills point to their deeds and to the open Lake policy and say those adjacent to the Lake are paying higher taxes because they are adjacent to the Lake. In an attempt to resolve ongoing disputes about who has access, in April 2001 the BMA began seeking feedback on a plan to lease the land below 1084' to adjoining landowners for $100 per year. Hardly anyone seemed to like the idea. People in the hills argued they should also have the opportunity to lease land, not just those who own property adjacent to the 1084' line. Even some of those property owners questioned the proposal's fairness and whether BMA had the legal right to do it. In October 2001 another controversy resurfaced over public access to Diversion Lake. Although the waterway is public, its banks are privately owned and public access is restricted by Medina county. Arguments over who should have access have been going on for over 80 years. In Texas, when a public river is dammed, the resulting lake is public property, but only people able to reach it legally have a right to use it. The Medina Ranch, while recognizing the water is public property, owns both sides of the River right down to the banks and wants to protect its private property rights. The Ranch granted the county an easement for County Road 271, and the county maintains a fence that blocks access to the Ranch at the bridge where the road crosses the Medina River. The only public access to the waterway is from this bridge. The bridge was replaced in the summer of 2001, and debate erupted when a new fence was installed in October with gaps for public access only two feet wide. In May of 2004 Medina county officials made a field trip to review the 2001 fence project when new complaints were received. Even without the fence, there is still no public parking available. Texas Parks and Wildlife Dept. attorney Boyd Kennedy said that although the Lake is public and boaters have the right to use it, there's no law that requires anybody to give public access to a public body of water. In April of 2003 the land ownership controversy erupted again when the BMA began testing its claim to ownership of all land below the 1084' contour line. The agency had received little support for its 2001 plan to lease land below 1084' to persons who had built structures on land they believed they owned, and it sued two Wharton's Dock residents for title and possession of the land under their homes. Residents all around the Lake began preparing for bitter legal battles. By July 2003, the BMA had completed surveys using extremely accurate global positioning satellites that clearly delineated where residents had built structures below the 1084' line. It also hired a researcher who concluded the land between 1072' and 1084', previously thought by many to be an easement, was owned by the BMA through fee simple title. Medina county tax appraisers agreed the BMA appears to have rightful claim to all property below the 1084' line unless landowners can show the property was purchased before BMA existed. BMA officials agreed that residents have a right to be angry, but not at them. They blamed the problem on developers, real estate agents, and county officials who allowed BMA land to be sold, platted, taxed, and settled. It seemed likely that persons whose land was condemned long ago for Medina Lake construction might have retained certain rights of ownership and/or use of the contested lands. It is not all that uncommon for landowners to be allowed to remain on and use land that is taken in condemnation proceedings. Whether or not such rights can be extended to hundreds of other persons when the original tract is subdivided is still a large unanswered question. More than 100 homes in Wharton's Dock subdivision alone are below the 1084' line. The BMA said it has the deeds, but attorneys for Wharton's Dock residents had a different interpretation of the same deeds, and indicated they would argue in court that the BMA's deeds only give them the right to flood the property. Residents formed a non-profit corporation, the Waterfront Property Owners Association, to advocate for the interests of landowners. In January 2004 the Waterfront Property Owners Association filed a petition for declaratory judgment, arguing that the BMA had embarked on a campaign to seize control of privately-owned waterfront property on Medina Lake. They were seeking, among other things, a declaration that BMA’s rights in the Contour Zone are limited to the right to flood in connection with the storage of water in Medina Lake for irrigation purposes. In November of 2004, an agreement was reached in a court-ordered mediation session that allows lakeshore landowners who voluntarily sign on to the settlement to have guaranteed access to the water and also allow them to fence off the shoreline against unwelcome visitors. Under the agreement, the BMA will convey to participating residents a perpetual easement to the land below 1,084'. In exchange for control of the waterfront, residents will pay an annual assessment fee based on linear feet of shoreline and also agree to have their septic systems licensed and inspected. Landowners had until March 1 2005 to sign on, and more than 300 did so. The ownership rights of those who did not sign on are still subject to challenge by the BMA. The pact did not address some major unresolved issues, including the validity of BMA's ownership claims, the agency's jurisdictional boundaries, and the extent of its regulatory authority over the Lake. In 2013, a court dispute between shoreline neighbors evolved into a new examination of the various claims of ownership of land below the 1084' line. John and Debra Lance, residents of the Redus Point subdivision, attempted to restrict access to a quarter-acre lakefront parcel previously used as a park. They built a pier, installed cameras, and began erecting a fence. Three other neighboring couples sued, seeking affirmation of their rights by easement to use the parcel. The BMA intervened in the lawsuit, claiming it owned the land below 1084', which encompasses the entire tract of land in question. On Oct. 10, Bandera county also intervened in the suit. In an interview with the Bandera County Courier on Oct. 9, County Commissioner Bobby Harris said "This is the biggest potential land grab in the history of Bandera county." The BMA claimed the Lance's deed to the property was fraudulent, and in a ruling on June 11, 2014, district court judge Keith Williams agreed. He found the Lance's presented a Deed Without Warranty with the intent to create the appearance of an actual ownership in the disputed area, and they had never acquired any actual ownership. They have easement rights as lot owners in the Redus Point subdivision, but "These easement rights do not give the Lances the right to exclude other lot owners from using any portion of the land below the flow line of the Lake." The judge did not find, however, that BMA owns the land. And so while the issue of ownership below the 1084' line may not be settled, it appears that in certain cases neighbors have recourse if their access is restricted by other neighbors. It is likely that future such disputes will be settled by reference to original deeds, which have many different provisions regarding access and ownership depending on what terms were originally negotiated with the landowner at the time the Lake was built. Indeed, this is a source of great confusion for landowners today - they may talk to a neighbor whose deed stipulates certain provisions and believe these provisions also apply to their own property, when in fact they may not. Use of Medina Lake Water While controversy swirls around access and ownership, the future of recreation at Medina Lake also remains in question. After Edwards Aquifer supplies became limited by law, area water purveyors had to look toward Medina Lake to help meet growing demand. The first version of a regional water plan offered by South Central Texas Regional Water Planning Group in 2000 suggested that through purchase and/or retirement of irrigated farmland and Aquifer pumping rights, more water could be left in the Lake to become Aquifer recharge (this was before scientists began to question whether Medina Lake actually provides any recharge to the Edwards). Under that scenario, Lake levels would generally be higher which would benefit recreation, but the farming segment of the local economy could be impacted. And there would be some other issues that would have to be worked out such as getting a recharge recovery permit from the Edwards Aquifer Authority. In the group's 2011 plan, a Medina Lake "Firm-Up" strategy was outlined that involves an aquifer storage and recovery project and/or an off-channel reservoir to firm up supplies. The 2011 plan did not officially include any supplies at all from Medina Lake, because the "firm yield" of the Lake is zero, meaning you can't depend on getting any water at all from it in droughts. In November 1999, the BMA board approved a long-term contract with the Bexar Metropolitan Water District to supply 10,000 acre-feet annually, increasing to 19,974 acre-feet by 2012. Bexar Met then executed a Design-Build-Operate agreement with United Water Services Corporation to build and operate a treatment facility. Bexar Met was dissolved in 2012 and the facility is now owned by the San Antonio Water System, which has not operated the facility since 2015. Water was picked up from the Medina River, then treated and distributed from a treatment plant that opened in February 2000 in southwest Bexar county. SAWS had considered such a project in the 1990s but declined to pursue it because of the issue with Medina Lake having no firm yield - SAWS decided to pursue other projects that would provide a reliable supply. In any case, when the Bexar Met system was merged with SAWS in 2012, it became SAWS' contract to manage. In June of 2023, SAWS filed a court action to free itself from the water supply contract inherited from Bexar Met. The contract has take-or-pay provisions, meaning that BMA gets paid whether or not the water is used, and by this time SAWS had paid BMA more than $28 million. The contract as written extends through 2049 and could cost SAWS an additional $78 million. According to the court filing, the Medina Lake water is water that "SAWS does not currently use, has not used for nearly a decade, and has no plan to prospectively use." In an interview with The San Antonio Report, Robert Puente, president and CEO of SAWS, said the maneuver is “not a lawsuit as we think of the lawsuit. This is a request for … a declaratory judgment - for the judge to look at the contract and declare that that contract is against public policy. A public entity should not be paying $3.3 million a year for nothing, right? It’s just not fair." The court action asks that a civil district judge mediate an end to the agreement. When more of Medina Lake's water became directed toward municipal uses in 2000, it was thought that maintaining water quality would likely become another controversial issue. It is not uncommon for gasoline-powered watercraft to be banned from water bodies that serve as a drinking water supply. Such a ban would surely have raised the ire of boaters, but the alternative could be higher treatment costs for municipal users. Another issue that seemed likely to surface is what to do about septic tanks that dot the shoreline and discharge effluent which ultimately reaches the Lake. Septic tank effluent contains nutrients and pathogens, and systems that discharge by gravity using a drainfield are usually prohibited near waterbodies. It was thought that it would probably become necessary to remove or replace such systems with ones that evaporate the effluent to the atmosphere or spray it on a landscape. Many of the existing septic systems were decades old and not much more than a homemade system of buried 50 gallon drums. These probably provide almost no treatment of septic wastes. Since SAWS no longer uses the water supply and has no future plans to do so, all these issues have faded. During the drought of 2006, some farmers who had always relied on Medina Lake water were forced to find other sources or stop farming. On June 19, BMA Board President Tommy Fey sent a letter to customers announcing that at their current rate of withdrawal, the District would be out of water to sell by the end of August. Although most of the major crops such as corn and cotton were already finished irrigating for the year, the situation caused difficulty for vegetable farmers who plant in the fall to make products available around Thanksgiving and Christmas. The drought of 2006 also confirmed that supply of water from the Lake is not reliable. During dry years, not all of the 20,000 acre-feet that SAWS has under contract is available. Conversely, during wet years, not all of it is needed. In August of 2008, an alliance of 14 small cities called the Texas Regional Water Alliance received authorization from the Texas Water Development Board to fund a study aimed at examining ways to firm up supply from the Lake during dry years and store excesses during wet ones. Some of the methods examined included storing water in small off-channel lakes along the canal, or injecting water underground for retrieval later. The idea was that if reliability and supply can be increased, the water could be available for Alliance member cities. Tremendous rains in the summer of 2007 filled the Lake to capacity, but two years later it was down to 25%. When drought came again in late 2010, it had recovered to about 75%, but as drought persisted through 2012 it then began a steady decline to levels not seen since the 1950s. In September of 2012, the dam gates were closed and water flow to the irrigation canal was cut off in an attempt to keep at least some water in the Lake in case it was called on for municipal use by San Antonio. Under the contract terms with BMA, SAWS pays a premium for Lake water but is also the last to be cut off when supplies are short. The increased revenue allows BMA to make system improvements it otherwise could not afford. In December of 2012, the BMA notified farmers that no water would be available for irrigation in 2013 until climatic conditions change. SAWS did call for water in 2012, but discontinued their plant operations in late May, citing water quality concerns with the remaining water in the Lake. Luckily for customers in areas that had been receiving Medina Lake water, SAWS was able to complete a number of interconnections with their larger system to supply those areas with Edwards water, an option that would not have been available to Bexar Met. In April of 2013, new controversy erupted when the BMA announced plans to complete a study of all legal and illegal water wells around Medina Lake and the wells' contribution to dwindling Lake levels. The Hondo Anvil-Herald reported that in response to questions from BMA Director Bill Hope about the possibly dubious nature of the study, BMA Director Will Carter said "If the Lake is being drawn out of from the sides by all this development around the Lake and we are the ones footing the bills and we are the ones who do not have water for irrigation, we need to know how the wells impact the Lake level." Hope pointed out that well owners are drawing water from the Edwards Aquifer, not the Lake, but Carter countered the water is possibly recharge that came from the Lake and said he felt the BMA needed to do the study. A second study was planned to determine the impact of reduced upstream flows into the Lake. "The study will determine how many tributaries in the basin have been dammed up to restrict water flow from the basin into the Lake," said BMA Business Manager Ed Berger. In October of 2013, the Bandera County River Authority and Groundwater District filed a lawsuit against the BMA to stop the studies. It asserted the BMA has "no jurisdiction whatsoever to exercise governmental authorities or groundwater investigations in Bandera County, Texas." In October of 2015 a district judge declined to kill the suit, rejecting BMA's argument the dispute is not ripe for adjudication because no true conflict has arisen. Greg Ellis, attorney for the groundwater district and former EAA General Manager, said "Obviously, we're very pleased. We're looking forward to the next hearing." In July of 2022, the dispute was settled when the BMA adopted a resolution saying that it agreed not to assert "regulatory authority over property in Bandera County." BMA acknowledged it has no authority over groundwater withdrawals in Bandera County and no regulatory authority to inspect private or public water wells that it does not own in that county. Attorney Greg Ellis said "People who live in Bandera County, right around the Lake, are not going to have to pay any attention to any comments, rules, or regulations or anything else that might come out of BMA." Infrastructure Issues For several decades, some major repair work was sorely needed on the Medina dam control structures. One of the ancient valves that controls releases from the dam was inoperable, and the other two were rapidly deteriorating and could have failed at any time. There wasn't any danger that a life-threatening wall of water could rush down the Medina River, but if they were to fail in the open position the Lake could drain in a matter of weeks; and if they failed in the closed position people who have rights to irrigate with the water would be unable to get it. The side of the valves under the Lake hadn't been inspected and it was unknown if they needed extensive rebuilding. Under the 1999 water supply agreement with BMA, the Bexar Metropolitan Water District agreed to address several infrastructure issues including:

In June 2000 a committee recommended a plan to initiate repairs to the gates in early 2001. Under the plan, Gate 3 was plugged and new outlet piping installed on Gates 1 and 2. The plan also included removing debris from in front of the gates on the upstream side of the dam. The work did not begin until 2003 and while it began during a wet spring, it continued into a very dry summer, and farmers were unable to get water through the gates that normally control releases. They were so desperate to get water that heavy equipment was brought in to chip a notch into the spillway and large pumps were used to send water downstream. Meanwhile, back at the valves, debris removed included telephone poles and an automobile. It took three months to install two new electrically operated, custom-made valves, but by November it was clear they were warped and leaking. Key parts had to be removed and sent back to the manufacturer for rebuilding. There was some finger-pointing between the manufacturer and the contractor who installed them, and the contractor's bonding agent eventually agreed to pay for the repairs. The valves had apparently been torqued too tightly during installation. After one of the valves was re-installed in mid-December of 2003, it still leaked more than 1,500 gallons per minute. In March of 2006, the BMWD approved a contract to draw up plans for installing an additional valve on each gate. The idea is the existing leaky valves can be used to regulate the flow of water from the dam, and the new valves will regulate the flow released downstream. In the early 2010s, under the leadership of BMA General Manager Ed Berger, vast improvements were made to the canal system that delivers Medina Lake water to 1,900 irrigators downstream. For decades, about 80% of the water that entered the canal was lost to evaporation, leakage, and theft. A September 1999 BMA report indicated that at that time 38,132 acre-feet had been released to the canal, but only 5,520 acre-feet had been sold. That means about 6.9 gallons were placed into the canal for every gallon sold. About 30% of the water diverted to the canal was lost to leakage in the first six miles of the canal alone. Another problem was that withdrawals operated on the honor system and there were no meters to record water usage. Some irrigators who use water from the canal took more than they paid for. In September 2000, the BMA received a $3.7 million loan from the Texas Water Development Board to line the upper six miles of the canal, a project that cost about $6.5 million. Since 2009, all deliveries of water are metered, which has eliminated the issue of farmers using water without paying. In 2012, Mr. Berger took advantage of low Lake levels to launch a program of replacing large sections of open canal with pipes, thereby completely eliminating loss and evaporation. The effort focused on stretches where the canals crossed sand formations and large amounts of water simply disappeared. Several holding lakes were also been desilted and improved - these lakes are used to contain water already in the canal when demand from farmers drops off, such as in the case of rain. Water can be diverted to these holding lakes and then sent to farmers when they need it. Also, the large main canal was cleared of vegetation and relined with clay where necessary, making it much more efficient at delivering water without losses.

The Flood of 2002 In July of 2002, the safety of Medina Dam was called into question when a stubborn low-pressure system parked itself over the region and much of south Texas received almost a year's worth of rainfall in less than a week. Water more than 12 feet deep crashed over the spillway and the level of Medina Lake rose to within inches from the top of the Dam. Normally, dams are not constructed to withstand water going over the top; and if that had occurred, there could have been significant erosion that might have undermined the structural integrity of the Dam. On July 5 BMA officials, engineers from Freese and Nichols, and state and federal officials inspected the Dam and there was disagreement about whether it was safe. The inspection party was missing an important member...Chau Vo, the State's top dam-safety engineer, had been inadvertently left in a hotel room. He organized his own tour later that day and concluded he could not be 100% sure there was no danger. He advised the Department of Public Safety, which issued a public warning. County Judge Nelson Wolff went on TV that evening to relay the DPS warning about the Dam's safety. It resulted in the complete evacuations of Castroville and La Coste. Wolff's action came under heavy criticism from residents and BMA officials who claimed it was politically motivated and that people were needlessly scared. A subsequent check of the Dam concluded it was safe, but a report prepared for the TNRCC by Freese & Nichols issued a few days later contradicted this conclusion. The State report said that if water had gone over the top of the dam there could indeed have been a massive failure. It concluded that DPS was correct to issue a warning and Judge Wolff was correct in relaying it on TV. On July 11 engineer John King of Freese & Nichols released a list of 20 recommendations that included early warning systems, assessment of scour potential in various areas of the structure, and examination of alternative methods to prevent overtopping of the Dam in the future. The controversy did not end there, however. On July 17 engineers hired by the BMA said the Dam could have withstood water going over it 16 feet deep. One thing was for sure...the fiasco pointed out major flaws in the communication system that is supposed to warn residents of danger. Subsequently, lawmakers issued calls for new statewide dam safety inspection programs and ordered the preparation of another safety report for Medina Dam. Two years later, in October of 2004, the state-ordered study concluded the Dam could topple over or slide downstream if overtopped by more than about six feet of water. Engineers recommended $2.7 million in improvements to stabilize the Dam and prevent erosion, including anchoring the Dam abutments into bedrock with cables and protecting the abutment's limestone foundation with several feet of reinforced concrete. By late 2006, the cost estimate had almost quadrupled to $11 million. With only about $3 million on hand for repairs, the BMA sought funding from federal sources and also from the Texas Water Development Board, but struck out on both occasions. In March of 2008, Bexar county announced it would commit $3 million to the repair costs, because a catastrophic Dam failure would cause widespread damage in the southern part of that county. More than 50 square miles would be flooded and Toyota's truck manufacturing facility would likely be under water, along with two of SAWS' major wastewater treatment plants. To secure the remaining $4+ million, Rep. Tracy King proposed a bill during the 2009 Legislative session to give the BMA credits with the EAA for water that leaves the Lake and becomes Edwards recharge. The idea was the BMA could sell these credits to fund repairs. This plan was widely viewed as a non-starter, because the recharge from Medina Lake was factored into the water budget when pumping permits were issued. A second version of the bill proposed that instead of issuing recharge credits for subsequent sale, the cost would simply be divvied up among downstream interests. The bill was approved by the House but never made it out of a Senate committee before the session ended. The issue was resolved, however, when $4 million for repairs was included in the state budget, and in June of 2009 local authorities were expected to move quickly to develop a required interlocal agreement and get the repair process underway. In March of 2010, contractor bids were solicited for work designed to make the Dam capable of withstanding an 11-foot overtop by floodwaters. Happily, a bid came in from the Austin Bridge and Road Company that was much less than the projected $11 million. For $3.7 million, the company installed 32 anchors that pin the Dam to the ground and also poured concrete aprons to keep the Dam from slipping and tipping. Work began in November of 2010 and was expected to take about a year to complete. In July of 2011, two workers were injured when equipment used to pump grout under high pressure failed, causing pieces to fly. In December of 2016 the BMA enacted new Dam safety measures, prohibiting the use of watercraft and other activities within 300 feet of both Medina and Diversion Lake Dams. Both are classified as "high hazard" dams, and the BMA has to have security plans in place and report those plans to the State. For these Dams, the issue is not so much a concern of Dam failure, it's just that dams are inherently dangerous places and people should stay away. There are also Homeland Security considerations. The new BMA rules provide that persons or entities found to be swimming, wading, bathing, fishing, using any type of watercraft or floating device, taking images, or conducting overflights by drones at a height of less than 400 feet shall be considered in violation and subject to a Class C misdemeanor and a fine not exceeding $150.

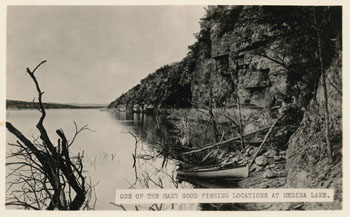

Medina Lake Photo Gallery The pictures below are organized to take you on a "virtual tour" from Medina Lake down to the far reaches of the canal system:

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||