|

|

The San Antonio River

Native American Uses and European Discovery

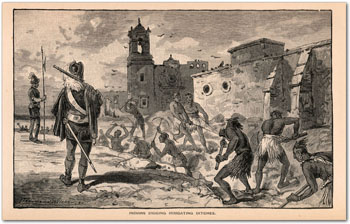

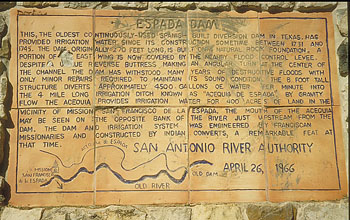

The Acequia Systems When the Spanish arrived for good in 1718, they immediately began constructing a system of irrigation ditches, or acequias, to divert water from the San Antonio River and San Pedro Creek to farmlands. At first the work was carried out by the missionairies themselves and settlers, but most building was eventually carried out using forced labor of Indian converts. Eventually five mission complexes were established, linked by seven acequia systems, between the headwaters of the San Antonio River and its confluence with the Medina River. The acequias served as San Antonio's water system for almost two hundred years and were the first municipal water distribution system in North America. They were remarkable engineering feats for their time, and some are still in use.

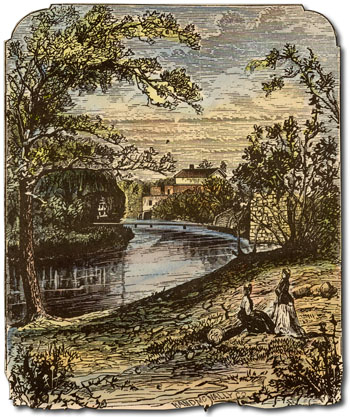

The 1800's: Beautiful Servant By all accounts, the San Antonio River before Edwards Aquifer wells were drilled was a large, crystal-pure, reliable stream, much unlike the murky trickle it became later on. George W. Bonnell described the situation in 1840:

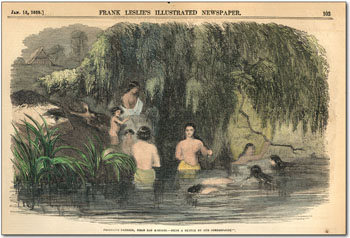

Few cities have had such an intense love affair or such an intimate relationship with their river as San Antonio. Year round bathing in the River was a San Antonio tradition and was described by Frederick Marryat in 1843: By 1850, San Antonio had made a servant of its River. It powered waterworks and mills, fed irrigation ditches, provided drinking water, put out fires, and carried sewage downstream (McLemore, 1980). In 1877 Harriet Prescott Spofford, writing for Harper's New Monthly Magazine, rode on one of the first trains to San Antonio and declared "On a more enchanting spot the eye of poet never rested. There is probably nothing like it in America." Spofford wrote:

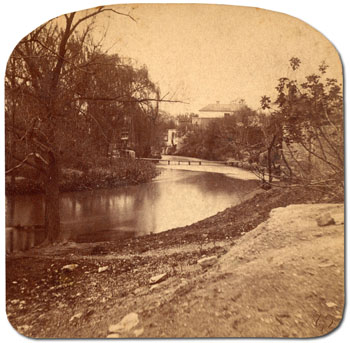

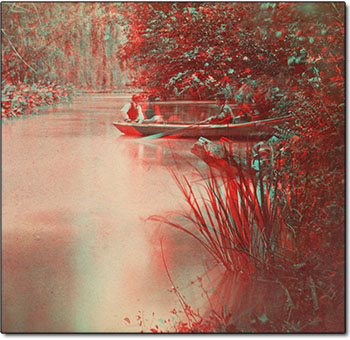

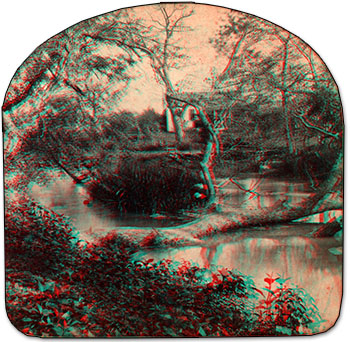

San Antonio River in 3D Get out your 3D glasses and view these San Antonio River anaglyphs, created from late 19th century stereoview cards. Click to enlarge - it's just as if you were really there.

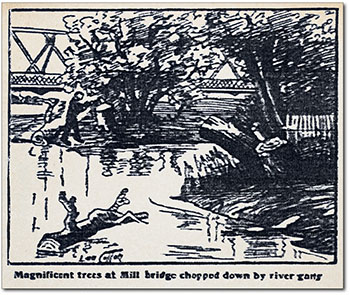

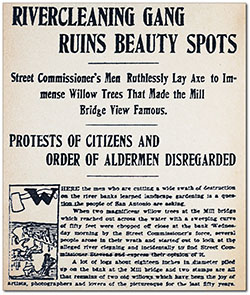

The River's Decline and the Early Beautification Efforts By the early 1890s, numerous artesian wells had been drilled into the Edwards Aquifer around San Antonio and the city began to rely mostly on wells rather than acequias for its water supply. The first geologists to accurately describe the Edwards pointed out that wells were impacting springflows that were the origin of the River (Hill & Vaughan, 1896). Since these wells were intercepting water and pressure that otherwise would have resulted in springflow, flows in the River began to decline seriously. In most years the River was just a trickle. By 1900, the bath houses were gone, swimming holes were too shallow, and there was not even enough flow to carry off garbage. Still, residents loved and protected their River. In 1904 city workers cut down two magnificent willow trees and an Express-News article on August 18th was titled "Rivercleaning Gang Ruins Beauty Spots". A public uproar resulted, and on August 20th a follow-up article entitled "Citizens Stop Ruin of Cherished River" outlined the promises of city officials to "beautify the stream and protect it in every manner possible." The city did its first riverbank landscaping shortly thereafter.

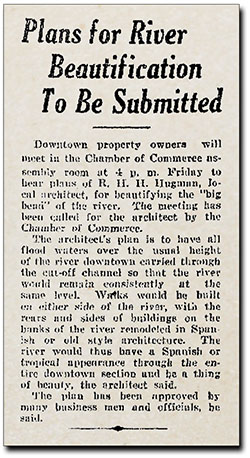

Public sentiment in favor of saving and beautifying the River continued to grow. On February 10, 1910, the Express-News headlines announced "Public Wants River to Receive First Attention". Later that year the Civic Improvement League began efforts to beautify sections of the River downtown by planting grasses, flowers, and shrubs. In September 1911, a small group of River-loving citizens formed the San Antonio River Improvement Association, and declared that a way to revive the River must be found. Mayor Bryan Callaghan, loathe to spend any public money on the River, grudgingly approved installation of a pump on an abandoned well in Brackenridge Park to provide the River some flow. Mayor Callaghan died suddenly in office in 1912 and was succeeded by reform-minded Augustus H. Jones, who immediately established a City Plan Committee and made River beautification his top priority. A flurry of plans followed. San Antonio architect Harvey L. Page devised a plan to line the River for 13 miles with reinforced concrete slabs, add decorative concrete bridges, and have numerous benches turn the banks into "a vast park". Using city money, River Commissioner George Surkey began building a modified version of Page's plan that established a uniform width for the downtown River channel with low concrete covered rock walls dubbed "Surkey's Sea Walls". Sodding and planting followed, and Surkey sought another artesian well to double the River's flow (Fisher, 1997).

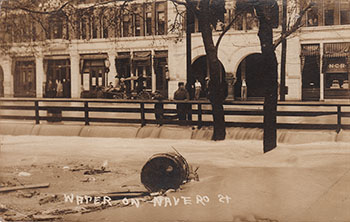

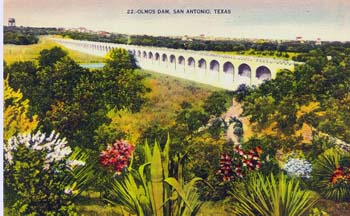

Flood Control Comes First Even as momentum toward River improvements was growing, six major floods occurred in the nine years between 1913-1921. Indeed, flooding was a way of life in San Antonio. The normal course of business was to scoop out the mud and try to get on with life. If a person had means to escape the flood-prone downtown area, they did. Consider the names of early subdivisions that became an alternative place to live when streetcars and automobile made them accessible: Terrell Hills, Tobin Hill, Alamo Heights. It is clear that what developers were selling was high ground. During this time, city officials gave serious consideration to concreting over the River and turning it into a sewer. Other proposals involved deepening and straightening and removing major landmarks and all vegetation, including carefully planted cypress trees from the beautification projects. Though many realized the danger, San Antonians also loved their River. When news leaked on March 31, 1921, that it might be destroyed it hit the citizens like a bombshell. City Hall was immediately besieged with irate visitors and contemptuous phone calls. The River was saved, but engineers warned of ruinous loss that could be caused by a 100-year flood. Such a flood occurred a few months later, before a flood prevention program was started. During the early morning hours of September 10, 1921, most of downtown was covered by 2-10 feet of water. More than 50 people lost their lives and downtown San Antonio looked like a war zone. San Antonians realized that before beautification projects could proceed much further, the city had to be made safe from its River. Olmos Dam and the Cutoff Channel After the great flood of 1921, it took almost three years for San Antonians to reach consensus about what should be done to control flooding. The two largest projects were construction of Olmos Dam in a narrow gorge above the River's headwaters, and creation of a "cutoff channel" so that floodwaters could bypass the Great Bend in the downtown area.

San Antonio River, 1836 and Today

When the "cutoff channel" was proposed betwen points A and B in the graphic above, some believed it would be a waste to let it sit empty while the "Great Bend" that meanders close to the Alamo carried the River's normal flow. The Great Bend took up seven acres of prime commercial territory, and real estate promoters thought it should be filled in and the new cutoff channel allowed to carry the River's flow at all times. San Antonians once again had to come to the rescue of their River, and numerous civic clubs formed such a well-defined counter-movement that city politicians clamored over each other to roundly condemn the idea of filling the bend. Citizens also organized to defeat a roadway that would have run parallel to the River near La Villita and completely overhang the River in some locations. After the cutoff channel was finally completed in 1929, attention could once again be turned to beautification of the River, and beautiful it did become! Robert H. H. Hugman and the San Antonio River Walk

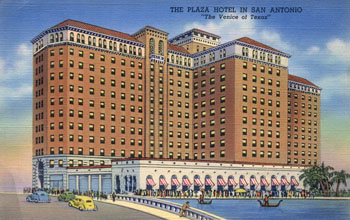

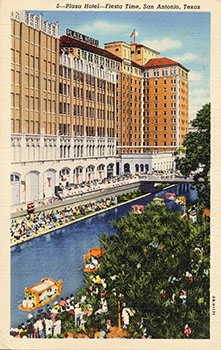

In 1936, Texas celebrated the 100th anniversary of the Republic, and the Daughters of the Republic of Texas made beautifying and preserving the natural charm of the River one of their centennial projects. It sparked an affirmation of public interest in the River. During Fiesta week, Plaza Hotel manager Jack White sponsored a River boat parade and more than 10,000 people crowded the banks, demonstrating that San Antonians had not lost enthusiasm for their River. White also saw that Hugman's commercially-oriented plan presented many more business opportunities than Bartholomew's. White organized the San Antonio River Beautification Committee, which hired Hugman and Edwin P. Arneson to prepare drawings for a project to submit for Works Project Administration (WPA) funding. The plan was estimated to cost almost $400,000. The Committee collected $40,000 from businesses along the River, secured some additional funding from the City, and got WPA funding for the remainder in place by the end of 1938. In 1939, after a full decade of debate and delays, work began on Hugman's San Antonio River Walk under the Work Projects Administration.

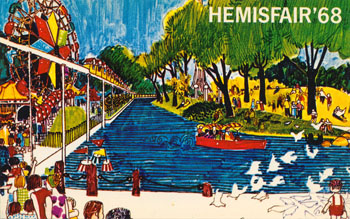

After work on Hugman's plan got underway, he supervised the project for less than one year before he was fired. The Great Bend of the River had always been mostly natural and pastoral, and powerful members of the Conservation Society were concerned about the new look. The fresh white limestone of the arched bridges, the concrete walkways, and the new theater stood in sharp contrast to the natural setting that existed before. Plantings had been temporarily removed and the channel drained, so there was an overall barren and disheveled appearance. In January 1940, the Society passed a resolution condemning Hugman's work as a "desecration of the beauties of San Antonio" and sent him a letter criticizing the "excessive stone work." Mayor Maury Maverick agreed with the critics and thought he would force Hugman to concentrate more on landscaping by cutting his supply of stone. When Hugman learned that materials for his project were being diverted to another WPA project, La Villita, he collected documentation and presented it to a judge who also sat on the River Project Board. Instead of supporting him, the Board unanimously dismissed him. Many of the elements Hugman intended, such as a curtain of water to screen the Arneson theater stage, were never built. On March 13, 1941, the Works Progress Administration formally turned over the River Walk to the City of San Antonio. There were 17,000 feet of new sidewalks, 31 stairways, 3 dams, 4,000 trees, shrubs, and plants, and numerous benches of stone, cement, and cedar. An estimated 50,000 people lined the River Walk on April 21 to dedicate the project and watch the first of what became an annual parade of boats. Even so, Hugman's work was highly under-appreciated and mostly deserted for several decades. Military personnel were banned from going there, and locals believed it to be seedy and dangerous after dark. During the HemisFair in 1968, the image of the River Walk began to be transformed, but it was several more decades before it really became a well-known international sensation. Even into the late 1970s, most locals considered it too dangerous to visit at night. Finally, by the early 1990s, it seemed the whole world knew about the River Walk and it was considered safe and welcoming.

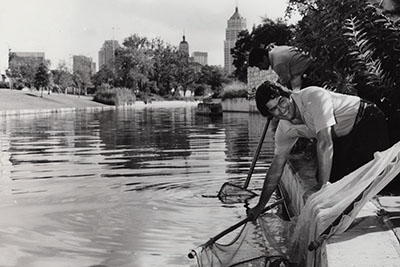

The River Today Today the world-famous San Antonio River Walk is the crown jewel of Texas and a major tourist attraction. Beautifully landscaped along its winding course through downtown, it is still most beloved by residents of the city. For decades, the entire dry weather flow was derived from wells in Brackenridge Park. But in June 2000, the San Antonio Water System began augmenting the River's flow with recycled water, allowing the wells to be cut off and reducing potable Edwards Aquifer water use. Afterwards, significant water quality improvements were documented and today the River flows stronger and cleaner than it has in decades. For example, in June of 2002 scientists from the San Antonio River Authority discovered a log perch, a darter that is highly sensitive to pollution, in the San Antonio River below Loop 410. In this area the River is almost completely water that started as raw sewage and was cleaned up at SAWS' Dos Rios Water Recycling Center. Up until the late 1980s poor treatment plant operations, poor stormwater quality, and influxes of dumped toxic materials resulted in a "dead zone" here that extended for many miles downstream. Officials said that finding a sensitive fish species such as the log perch indicates SAWS' treatment plant operations have been vastly improved and stabilized, the City's stormwater control program has been effective, and residents have done their part by ending their dumping of anti-freeze, oil, and household chemicals that kill fish. In recent years, in addition to the log perch, biologists have found other sensitive species such as stonerollers and long-eared sunfish. The River is now rated relatively highly on a scientific index that measures biotic integrity, and biologists expect the sensitive species to continue migrating toward the downtown area.

The Bacteria Issue One water quality parameter of current concern is coliform bacteria. The Texas Natural Resource Conservation Commission (now the TCEQ) and others have identified high coliform bacteria counts as a water quality concern, so contact recreation is not supported in the San Antonio River (TNRCC, 1996). These bacteria live in the intestines of warm-blooded animals are are not usually in themselves harmful, but they are used as an indicator that other harmful pathogens may be present. There are many possible sources for the bacteria, including sewer line leaks, agriculture, urban runoff, and wildlife. The regulatory levels for bacteria are based on risks to human health, but they are lower than what is often found in nature, so meeting them may not really be possible or desireable, unless we are going to get rid of all the birds and raccoons. For the San Antonio River, a primary source of bacteria was well known: the San Antonio Zoo. For many decades the Zoo discharged up to five million gallons a day of water that first was used in exhibits or for washing enclosures. The very heart of the Clean Water Act is that every single discharge of water must be treated to acceptable standards and permitted before release, and no one has ever really been able to explain why the Zoo seemed to be the nation's only exception. When the region's famous fish farmer Ronnie Pucek did something very similar - he routed water water through fish tanks and then released it to the Medina River - the state shut him down because he didn't have a wastewater discharge permit. In any case, a Watershed Protection Plan completed in 2006 for the San Antonio River Authority determined that treatment of the Zoo's discharge would bring most of the upper San Antonio River into compliance with state criteria, except under periods of prolonged wet weather when bacteria loads are more influenced by urban runoff (Miertschen, et al, 2006). In June of 2014, an ultraviolet (UV) disinfection facility began to treat the Zoo’s discharge and so far it has worked very well at killing bacteria. However, data collected so far has indicated the modeling conducted for the Watershed Protection Plan was wrong - downstream of the Zoo the River continues to exceed the regulatory limits for bacteria.

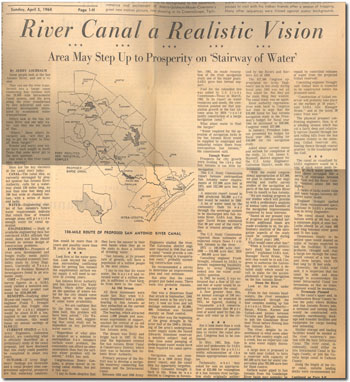

Whose River is it Anyway...? In 2001, a long-standing property dispute between the City and River Walk tenants appeared to be headed for a very interesting court battle. A portion of the funds the City uses to maintain the River Walk comes from rents charged to restaurants and bars who place tables along the walkways and kiosks near the water's edge. Several businesses, claiming that rates were too high and inequitable and that funds were not used for River Walk maintenance, had not been paying rent for as long as 12 years. Moreover, the businesses claimed they owned the land in question and they had deeds dating back to Spanish colonial times to prove it. The City claimed the businesses only owned land up to the edge of their buildings, since the walkways and kiosks weren't created until the River Walk was built in 1939. There did not appear to be any way for the businesses to win, even if they won in court, because in any event the City could simply condemn and take any land that a jury decided belonged to the restaurants. And any money the businesses might receive as compensation could be recovered by the City through even higher rents. In August 2001, just before the trial was to begin, the parties reached a deal in which the City obtained clear title to the lands, and tenants got more equitable rents, long-term leases, and seats on an advisory panel that would have a say in how revenues would be spent. Beyond the Great Bend Many tourists and even most local San Antonians are unaware of the River Walk's complete extent through downtown. Most think of the River Walk as just the "Great Bend" area where the floodgate has allowed hotels and restaurants to develop right along the River's banks. But the River Walk actually extends much farther. If you are visiting San Antonio or you are a local going downtown, you owe it to yourself to wander outside the Great Bend and see the rest of the River Walk. The north section extends past the floodgate up to the Pearl Brewery, past office towers and attractions like the Southwest Craft Center and the Museum of Art. The southern portion winds through the historic King William district where you can stroll past many graceful 19th century mansions. Until 2011, the River Walk ended at Guenther Street, where the offices of the San Antonio River Authority offices are located. In the spring of that year, a connection was opened to south that now extends 10 miles to Mission Espada. In the 1960s, an ambitious plan was advanced by the San Antonio River Authority to turn the River into a barge canal. SARA was originally formed by the Legislature in 1937 as the San Antonio River Canal & Conservancy District, and their primary purpose was development of a navigable waterway connecting San Antonio with the Intracoastal Canal. To that end, they developed a visionary plan for a 150-mile straightened and deepened channel with a series of locks and dams. In the 1940s, floods forced SARA to adopt other priorities, and in the 1950s droughts brought into question whether the canal would have sufficient water. The plan languished until 1961, when SARA and powerful legislators like Henry B. Gonzalez became convinced that wastewater return flows were the answer. A U.S. Study Commission report in 1962 concluded that San Antonio's growing population "could justify construction of a barge navigation canal", and it projected that by 2010 San Antonio would be discharging a staggering 380,000 acre-feet of water per year, more than enough to make the project viable.

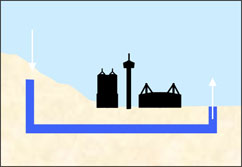

By the mid 1960s, newly completed interstate highways vastly improved transportation and made the River Canal idea seem wacky. There would be little need for trucks to offload in south Bexar county and send their cargo on a slow float to the coast when they could simply keep driving and be there in two hours. The River Canal would also have been unusable during floods, and a nationwide awakening to the environmental impacts of such projects was underway. The plan was abandoned and largely forgotten. The wastewater return flows envisioned in 1962 by the Study Commission report never materialized. Because of conservation, reuse, and limits on Edwards Aquifer pumping, San Antonio's actual treatment plant production in 2010 was 148,779 acre-feet, less than half of the volume projected in the 1960s. Urban development in the watersheds above Olmos Dam has led to larger, more frequent floods in the Olmos basin area. With more impervious cover, stream straightening, and stream channelization, waterways are able to deliver more water downstream faster. The Olmos Dam and the "Great Bend" cutoff channel can no longer ensure that floodwaters won't threaten downtown San Antonio. The San Antonio River Tunnel is the larger and longer of two tunnels designed to protect the downtown area by diverting floodflows 150 feet underneath the City. It took ten years to build and was completed in December 1997 at a cost of $111 million. The tunnel is about three miles long and passes almost directly underneath the Alamo! The inlet shaft is 24 feet in diameter, and water enters by overflowing from the San Antonio River. The outlet shaft is 35 feet in diameter and is at a lower elevation than the inlet, so the pressure of water coming in forces water out the other end, where it reenters the San Antonio River. When not being used for flood control, water can be recirculated through the tunnel and used to augment the flow of the San Antonio River in the River Walk area. The tunnel was put to the test during record 100-year floods in October 1998, and it functioned beautifully. After the floods subsided, divers found lots of beer cans and 5" crawfish, but no damage to the tunnel. When the River Tunnel was completed, it was thought the main channel outside the Great Bend area would be afforded enough protection from flooding that development could occur at River level, as on the Great Bend. However, the 1998 storm caused major flooding along the main channel and it became clear that new development right at River level along these stretches would probably not be possible.

The inlet structure is visible from Hwy 281 S. just before the Josephine St. exit at the southern tip of Brackenridge Park. The outlet structure is an engineering marvel that is an attraction in itself! San Antonio has a second flood control tunnel that handles floodwaters from San Pedro Creek. A Bold Vision: The San Antonio River Improvements Project By the late 1990s, the fabulous River Walk was almost 60 years old and in need of many structural repairs and improvements. An organized effort to revitalize the River began in 1998 when Bexar County, the City of San Antonio and the San Antonio River Authority created the San Antonio River Oversight Committee. Civic and neighborhood leaders were appointed to the Committee and given the responsibility of overseeing the planning, design, project management, construction, and funding necessary to complete improvement projects. The Committee produced a bold new vision for the San Antonio River that proposed major improvements in three separate areas:

Together, these three projects will create a River that is much more than a tourist attraction in the city's center. The vision is for a 15-mile long corridor that will serve residents with hiking and biking trails, natural retreats, new bank-level urban development, and new links to existing communities. Phase I: The Downtown Reach On January 31, 2000, a $12.5 million project to make numerous major repairs and improvements between Houston St. and Lexington Ave. was launched. Work involved installation of a reinforced concrete bottom in the River, improved access from nearby streets, flood control measures, and new lighting and landscaping. Mayor Howard Peak said "Even when this project is completed, all the work needed on the River won't be close to being done."

September 2001: The River Link Park opens On September 30, 2001, the Civic Center Riverlink Project was dedicated, marking the opening of a new city park that connects the River Walk to the City's historic center. The site at the corner of Soledad and Commerce Streets used to be a parking lot; now it is beautifully landscaped and terraced, dropping 16 feet to River level. The park features secluded niches for retreat, each with details like weeping walls and water wheels. Engraved stone describes the historic evolution of the River. The park took nine years of planning and was financed through a $3 million 1999 bond package. Completion means that now the hotels, shops, and restaurants most often frequented by tourists in the northern River Walk area are linked to Market Square, Main Plaza, and San Fernando Cathedral.

March 2002: Refurbished Downtown Reach reopens On March 18 2002, the newly renovated stretch of the River Walk between Lexington and Convent Streets reopened after 13 months of work. Major repairs were performed on cracking retaining walls and eroded banks. New benches and trees were crafted of concrete and made to look like wood by artist Carlos Cortes. New mosaic tile murals, punched copper lampposts, and new fountains flowing under walkways and into the River were also added. A new park at Augusta and Convent Street was created, with walkway patterns that adhere to the spirit of Robert Hugman's original designs. The park also has a fountain made from porous Edwards limestone.

Phase II: The Museum Reach In the Museum Reach, 1.3 miles of overgrown and inaccessible River bottom was transformed into a vast extension of the existing River Walk. On May 30, 2009, the Museum Reach officially opened. There are 25 new River access points along 3.4 miles of new walkways, along with four rest stop/overlook locations and numerous public art installations. It is hoped these improvements will be a catalyst for a vibrant urban renewal in an area of town that has traditionally been rather stark and industrial.

Previously, the River Walk ended near the Municipal Auditorium at Lexington Street, where the water ends in the above left photo. A structure across the River in that location is called the Hugman Dam. It was built as part of the original River Walk to create a constant water level elevation through town. In the construction photo above, the large black pipes were being used to deliver water to the downtown section while the upstream reach was drained for construction.

Phase III: The Mission Reach Improvements in the Mission Reach have focused on restoring the River's natural environment and enhancing the communities along the River's banks, not on amenities for tourists. Between downtown and Loop 410, almost all of the River was straightened, denuded of all trees, and the banks lined with large boulders and rip-rap in the 1940s and 50s for flood control, so that floodwaters could quickly leave the area. For decades, the general appearance was more of a drainage channel than a natural river. Only one short section of the River escaped these "improvements" and is still in its natural condition. Nowadays, engineers and environmental scientists know that you don't really have to ruin a river to get flood control benefits, so the plan is to put the rest of it back sort of the way it was. Newly created stream meanders and new landscaping and trees will create a much more natural look and feel.

Restoration work began on a portion of the Mission Reach in 2009, but in May it was learned that costs had been grossly underestimated, and it was unclear where funding would come from. The original price of $127 had increased to more than $233 million. In June of 2009, Bexar county commissioners announced they would use flood control funds to keep work on the Mission Reach going, with the hope that congressional representatives would eventually be able to secure adequate federal funding. By August of 2009, area congressmen had secured a total of $45 million in federal stimulus funds for the project, enough to keep work going. In the end, the county agreed to fund the entire project, with hopes that some costs could eventually be recovered from federal sources. In the spring of 2011, the first stretches of the Mission Reach opened for public access, and it wasn’t long until a full-blown kerfuffle erupted over the issue of paddling canoes and kayaks on the River. Making the River open to paddling was part of the original design concept for improving usability and public access, but the project is first and foremost an Army Corps of Engineers flood control and ecosystem restoration project. When doing the design, the Corps was not authorized to consider recreation. Even so, SARA worked to get some chutes incorporated in the dams that were intended to allow small watercraft to pass. In June 2011, when some kayakers from the Alamo City Rivermen were invited to test them out, it became clear they, uh, didn’t work. They were too short and too steep to be navigated by a standard length canoe or kayak. Riverman Gib Hafernick said “It does not look like they were talking to the paddlng community.” Another bone of contention was the issue of having to first obtain a city permit before getting on the water. There are many places in Texas, such as Town Lake in Austin, where canoers don’t need permits. When the issue got some press coverage, the city agreed the requirement was onerous and the Parks and Recreation Department simply announced that permits were no longer needed. Fixing the chutes was more complicated, however. SARA hired a consultant to look at options to make them more paddle-friendly and by November of 2012 had built new chutes that work for small boats even at low water levels. During a test before opening them to the public, Hafernick remarked "what they have is impressive." The new chutes are gently sloped and the surrounding waters are calm, so canoers can travel in both directions, using the chutes for portage going upstream. Six new bicycle sharing stations were also opened in November 2012, adding to the River's growing suitability for many types of recreation.

In the spring of 2011, the first stretches of the Mission Reach opened for public access, and it wasn’t long until a full-blown kerfuffle erupted over the issue of paddling canoes and kayaks on the River. Making the River open to paddling was part of the original design concept for improving usability and public access, but the project is first and foremost an Army Corps of Engineers flood control and ecosystem restoration project. When doing the design, the Corps was not authorized to consider recreation. Even so, SARA worked to get some chutes incorporated in the dams that were intended to allow small watercraft to pass. In June 2011, when some kayakers from the Alamo City Rivermen were invited to test them out, it became clear they, uh, didn’t work. They were too short and too steep to be navigated by a standard length canoe or kayak. Riverman Gib Hafernick said “It does not look like they were talking to the paddlng community.” Another bone of contention was the issue of having to first obtain a city permit before getting on the water. There are many places in Texas, such as Town Lake in Austin, where canoers don’t need permits. When the issue got some press coverage, the city agreed the requirement was onerous and the Parks and Recreation Department simply announced that permits were no longer needed. Fixing the chutes was more complicated, however. SARA hired a consultant to look at options to make them more paddle-friendly and by November of 2012 had built new chutes that work for small boats even at low water levels. During a test before opening them to the public, Hafernick remarked "what they have is impressive." The new chutes are gently sloped and the surrounding waters are calm, so canoers can travel in both directions, using the chutes for portage going upstream. Six new bicycle sharing stations were also opened in November 2012, adding to the River's growing suitability for many types of recreation. On May 25 of 2013, portions of the Mission Reach, some of which were not even open yet, suffered catastrophic damage when San Antonio received its second-highest daily rainfall total on record. More than nine inches of rain fell in the north central part of town, causing more than $3 million in damage to the public project. Damage to private property was extensive as well, with 14 homes destroyed in the Mission Espada area. Residents blamed the recent changes to the River and at public meetings afterwards were cool to buyout plans. Some have been on their land for many generations, since shortly after San Antonio was first settled by Europeans in 1718, and in public meetings afterwards they made it clear they don't relish the prospect of losing their property for future flood control. By August of 2013, the county had approved spending $5.5 million on appraisals, engineering fees, environmental assessments, and buyouts of property. The cost was expected to rise as property assessments are completed.

A Walk on the Wild Side South of Loop 410, the San Antonio River quickly becomes a wild and dangerous place with steep banks, thick vegetation, rapids, and endless other hazards like an irrigation dam and debris. In August 2001, four visitors launched a canoe at Interstate 37 and planned on several hours of paddling to where the River crosses Loop 1604. Their canoe hit a rock and they ended up stranded on rotting logs and trash, trapped by steep bluffs, their only company being snakes and clouds of insects. Rescuers located them about 3 a.m. but the rugged terrain prevented their rescue until after daybreak.

A Problem One of the problems on the San Antonio River in the urban reaches is....trash. Vast numbers of plastic bags and all manner of refuse dangles from tree branches after rain events and can be quite unsightly. The problem is especially evident in the Olmos Basin. In 2014 the San Antonio River Authority secured $60,280 in grant funding to be used in researching the location and sources of trash pollution. The information gathered helped determine the feasibility of installing a trash collection system in Olmos Creek and its tributaries and it helped identify other measured that could be employed such as public education.

In March of 2016, Master Naturalist Lissa Martinez explained to an Express-News reporter that to understand the value of Olmos Creek, you have to look beyond the trash. Intact riparian ecosystems offer large benefits for water quality and urban wildlife, but Olmos Creek is largely degraded by erosion, invasive plants, and litter. There was new hope that a 14-year old plan to improve Olmos Creek might finally get underway in 2017. A stream restoration plan developed by the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, the city of San Antonio, and the San Antonio River Authority would remove and replace invasive plants, create more shade over the creek, and address erosion. The area to be upgraded reaches from the San Pedro Driving Range to the Olmos Dam. A 50-foot wide buffer of bottomland hardwood forest, which is crucial for water quality, would be added in most of the reach and would be 300 feet wide in some places. With the results of its 2014 study in hand, the San Antonio River Authority determined it would wait until the restoration is complete before installing a trash collection system so as not to conflict with the restoration. But Wait, There's More River...! When most people think of the San Antonio River, they think of the River Walk and tourists. But below San Antonio, the River meanders across the Gulf Coastal Plain for over 150 additional miles. Along the way it supports diverse ecosystems, provides water for farms and ranches, and links the cities of Floresville, Falls City, and Goliad. It is one of the few rivers in Texas that has no major dams, so no large reservoirs have inundated the channel or adjacent lands. In the upper stretch of the River just below San Antonio, the channel is mostly characterized by a nearly homogenous U-shape with a sandy bottom and sand or silt banks (Cawthorn and Curran, 2008). An exception is just above Falls City, where a five mile stretch of the River is underlain by a bedrock outcropping that creates a unique area with complex riffle sequences and picturesque waterfalls. Beginning south of Loop 410 and continuing to Goliad, the channel is deeply incised and there are steep banks as high as 40 feet. The depth of the channel in relation to surrounding land is the reason that Spanish missionaries never attempted to build irrigation aqueducts in this stretch as they did in San Antonio. South of Goliad, the River has lower banks and the gradient in land surface elevation lessens, so there are more meanders and a general widening as the River gently approaches the coast. In any stream, flow is known as the "master" variable, because the timing and magnitude of flows affects everything, including habitats in the river and the riparian zone, the shape of the river channel, and water quality. "Base flow" is the part of the flow regime that represents normal flow conditions between rain events. Very little is known about what the natural flow conditons in the San Antonio River were like before Edwards wells were drilled. We have only a handful of narrative descriptions and no direct flow measurements. We know that in the first few decades after regular measurements began in 1928, flows in the River were characterized by perennial base flows and flashy flow conditions during large rainfall events. Some of this base flow came from San Antonio and San Pedro Springs during times when pressure in the Edwards was high enough to cause them to flow, and a great deal of the base flow volume measured in the early years also came from Edwards wells that were allowed to flow at all times. This was a typical practice in decades past. In it's 1936 Water Supply Paper 773B, the United States Geological Survey decried the large amount of waste from flowing artesian wells, and in 1951 the head geologist at the USGS in San Antonio said that 48 million gallons per day were flowing down the San Antonio River from free-flowing wells. As San Antonio grew, springflows became non-existent in almost all years and flowing Edwards wells were controlled or plugged. Yet base flows in the River have notably increased, especially since about 1970. It is often been supposed that higher base flows have resulted from San Antonio's treatment plant discharges. It is not really necessary to speculate about this question, because there are excellent records of treatment plant discharges since San Antonio's plants were first constructed in 1930. A careful examination of the data does not really bear out the assertion that treatment plants have caused an increase in base flow. The discharge volumes are clearly insufficient to account for the observed increase. Today's treatment plant discharges have essentially replaced springflows and artesian well flows but have probably not added much additional volume beyond that. There has been a slight increase in average rainfall since 1970 but there has not been enough additional rain to explain the large increase in flows. The most likely causative factors to explain higher base flows are urbanization and range management in the watershed. Today, hundreds of square miles of concrete and impervious cover result in runoff where almost none would have occurred previously, and there are many thousands of acres where range management practices also likely contribute to additional runoff. In addition to higher base flows, urban growth and poor land management upstream has also meant that peak flows during flood conditions are now higher. The trends toward higher base flows and higher peak flows have both led to a general widening and deepening of the stream channel and more erosion on the banks. In turn, increased erosion has led to more Large Woody Debris (LWD) in the River that is sourced from the banks during failures or high-flow events (Bio-West, 2008). Such debris is not necessarily a detriment to aquatic habitats - it can create diverse in-channel habitats for fish and other aquatic creatures. While LWD can actually be beneficial, the increase in base flows above natural conditions may be having negative environmental impacts. With higher flows, suspended particles are always in motion and never settle to the bottom, so silt and mud layers don't have a chance to develop. These layers are very important for a large array of organisms that form the base of the aquatic food chain, including worms, mussels, snails, crayfish, and beetles. Even so, biologists believe the San Antonio River is generally faring much better than most other Texas waterways and today is ecologically sound. There has been an increase in the number of non-native species found, but the overall fish assemblage has remained relatively intact (Bonner and Runyan, 2007). The main flow-related concern for the River is extreme low-flow conditions that can occur in the summertime. As mentioned above, a large percentage of the River's flow comes from SAWS' water recycling plants, this is especially true when it is hot and dry. At times, up to 70% of all the water produced by SAWS' plants is diverted by CPS Energy for use in their electrical generation cooling lakes, and there's not much left over for the River. During these times the aquatic habitats and organisms in the River can become stressed, but so far they appear to be resilient and capable of bouncing back. Extreme stress by heat and low flows once in a while is not altogether a bad thing. Such cycles occurred naturally and the native species are adapted for it, while the undesireable non-native species that we would prefer not to have in the River are killed off. About 10 miles above the Texas coast, the San Antonio River loses its identity when it confluences with the Guadalupe River. Near Tivoli, an inflatable dam know as the Saltwater Barrier was constructed by the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority in 1965. When activated during low-flow conditions, the dam allows river flows to pass through but prevents salt water from encroaching upstream. The structure is essential to safeguarding water supplies for agricultural, industrial and municipal drinking water use.

Conquista Bluff overlooks a historic crossing and is located on private property about three miles southwest of Falls City. A sandstone escarpment caps a thick clay layer and rises about 80 feet above River level. Because the River bottom here is bedrock instead of alluvial deposits, flows could not create a deep incision. Instead, the River widened. The flat bedrock substrate and shallow nature of the River created an ideal place for people and goods to cross before bridges were constructed. It was used for thousands of years by native tribes and later by Spanish explorers and early settlers. Current residents report that in decades past, there was a long tradition of swimming and recreation here. The site is now closed to the public. Just upstream around a horseshoe bend, Mays Crossing was another important point for crossing the River. Ensuring Flows for the Future In 2001 the Texas legislature had a great idea: figure out how much water should be in the River to support a sound ecological environment. In 2007 the Texas legislature had another great idea: figure out how much water should be in the River to support a sound ecological environment. Although these two legislative endeavours have an identical goal, there are some key differences in their approaches, strategies, and scopes. The first program, known as the Texas Instream Flow Program (TIFP), was created under Senate Bill 2 in the 2001 legislative session, and it is also known to river geeks as the SB2 program. The Legislature directed that state agencies would determine flows necessary for a riverine "sound ecological environment“ by conducting extensive field analysis, and that stakeholder input would be considered. It also provided zero funding for the extensive scientific analysis that would be necessary. The second program is known as the Environmental Flows, or E-Flows program, and it was established under Senate Bill 3 in 2007, so it is also know as the SB3 program. Under this program, regional stakeholders are the primary drivers, not the state agencies. The other main difference is the SB3 program includes freshwater inflows to the bays and estuaries, not just instream flows. The Legislature directed that a Stakeholder Committee and an Expert Science Team be created for each major river basin in Texas. The scientists are charged with determining the flows necessary to support a sound ecological environment in both the rivers an bays using the best available science, thereby eliminating having to wait indefinitely for funding and extensive analysis under the SB2 Instream Flows program. They are instructed to make flow recommendations by considering the environment only, not other needs. The SB3 Stakeholder Committee is charged with examining the scientist’s recommendations, then formulating their own recommendations by balancing both human and environmental needs. Both sets of recommendations are then submitted to the Texas Commission on Environmental Quality (TCEQ), which engages in a rulemaking process, considers input from any interested parties, and promulgates new rules regarding environmental flows that are to applied to any new surface water rights applications. The entire E-Flows process is intended to be iterative and subject to periodic review, so that if new science becomes available under the SB2 Instream Flows program, it can be incorporated into flow recommendations and rules. In the San Antonio/Guadalupe basin, the SB3 E-Flows process started in the fall of 2009 with the appointment of a Stakeholder Committe comprised of representatives from environmental organizations, municipalities, industries, water purveyors, and other interest groups. The Expert Science Team was appointed in the spring of 2010 and conducted an intense one-year evaluation, mostly of existing data, but which did also include much new science. They formulated flow recommendations for 16 gage locations in the San Antonio/Guadalupe basin, along with recommendations on inflows to the bays and estuary system, and submitted their report on March 1, 2011 (get the report here). On September 1, 2011, The SB2 Stakeholder Committee submitted their own report, which included some adjustments to the Science Team recommendations to make allowances for planned water projects and other concerns the stakeholders had (get the report here). As mentioned above, the main flow-related concern for the San Antonio River is occasional extreme low flows in the summertime when vast amounts of water are being diverted for electrical generation. The recommended strategies to maintain adequate flows included voluntary set-asides, dedication of wastewater flows, and dry-year options. The Stakeholder Committee was also directed by the Legislature to keep working after their report was submitted and develop a Work Plan for the future, a prioritized list of knowledge gaps and additional studies they felt were needed to improve and refine flow recommendations. Before the SB3 process started, and in light of the state’s failure to fund any SB2 studies, the San Antonio River Authority (SARA) stepped up to the plate and volunteered to fund the extensive studies envisioned in the SB2 Instream Flows program. Studies like this take a number of years and involve an incredible amount of fieldwork to scientifically link flow rates and response in aquatic habitats. SARA and their contractors sampled some 12,000 fish under a variety of flow conditions, did habitat and substrate mapping, hydraulic data collection, water quality measurements, riparian zone analysis, and sediment transport studies. The draft flow recommendations and lots of useful data were available to inform the SB3 Science and Stakeholder Committees. The good news is that almost all the SB3 regional stakeholders agreed on goals for flow in the River and strategies to ensure they occur. Amongst the committee of 25 persons, 28 votes were taken to approve recommendations on flow regimes and other matters, and 17 of these votes were unanimously in favor. In the other 11 votes, no more than 3 votes were cast against. In addition, the scientists and stakeholders generally agreed on things. In other basins where the SB3 process has occurred, there have been major disagreements between and among stakeholders and scientists. In March of 2012, the TCEQ released draft rules which they proposed to publish for public comment in the Texas Register prior to final adoption. Stakeholders were alarmed to find that TCEQ staff had eliminated many of their recommendations. Both the Science Team and the Stakeholder Committee had recommended a full suite of flows that were based on the state’s own scientific guidance documents. These included minimum subsistence flows, a range of seasonal base flows, a tier of pulse flows that occur after rain events, and overbank flows that are important for riparian zone habitat and stream channel morphology. The Stakeholders had also recommended an environmental “set-aside” of 10% for new permit applications. The TCEQ staff proposal eliminated the set-aside, the overbank flows, and most tiers of the base and pulse flows. Changes were more dramatic on the Guadalupe River side of the basin, where the Guadalupe-Blanco River Authority has several new off-channel reservoirs planned. When the Stakeholders were struggling to formulate their recommendations in marathon all-day/half the night sessions, GBRA objected to almost everything; it seemed that if the group desired chocolate donuts, GBRA would demand glazed. At a meeting of TCEQ Commissioners on March 28 to approve the rules for publication, Stakeholders packed the room to urge the Commissioners to instruct that staff revise the proposed rules to more closely reflect the Stakeholder recommendations. Before it was over, the Commissioners had adopted an amendment that left the door open for TCEQ staff to make revisions that would return many of the Stakeholder recommendations to the rules package. After the March 12 hearing, a public comment period followed, and thousands of comments were submitted which mostly supported revisions that would more closely mirror the Stakeholder recommendations. On May 25, the Stakeholder Committee completed its Work Plan and submitted it to TCEQ so it would be available during the period that rules might be revised (download the Work Plan here). During this period the TCEQ was invited to one of the final Stakeholder work sessions to make a presentation regarding the proposed rules. Most Stakeholders felt that TCEQ had disregarded their recommendations without any justification, and they were hoping to hear some. They did not - they only heard a reiteration of the proposal. Stakeholders pointed out that TCEQ staff was present at all the Stakeholder meetings, and it could have at least signalled they were recommending things that had little chance of receiving TCEQ approval. TCEQ pointed out the Legislature directed that it "consider" Stakeholder recommendations, not necessarily accept them. Most Stakeholders ended up feeling like they were sort of tricked into spending a lot of time and effort doing something that TCEQ knew all along it was simply going to trash. They felt that TCEQ undermined the Legislature's intent for the process to be mostly Stakeholder driven. After the public hearing and the comment period, the TCEQ staff declined to make any significant changes to their initial proposal. The prevailing opinion among most that are knowledgable about the workings of the water business around here is that TCEQ staff is highly intimidated by GBRA - it appeared that TCEQ simply acquiesced to pressure from that agency. When TCEQ Commissioners met to adopt the new rules on August 8, Commissioner Carlos Rubenstein proposed an amendment to return at least one of the protections to the Guadalupe River, a seasonal high pulse flow, which the great majority of Stakeholders and public comments supported. That amendment was adopted, and the final rules became effective on August 30, 2012 (download them here). In the end, the whole SB3 process left most Stakeholders dissatisfied with both the outcome and the process, questioning whether Texas really has any commitment to protect her rivers and bays. While the State's commitment to the San Antonio River is questionable, that of San Antonio is not. In December of 2013, the San Antonio Water System applied to the State for an authorization to use 50,000 acre-feet of its treated effluent for instream flow purposes. Water would be allowed to remain in the stream, supporting aquatic habitat and uses like recreation along its 250-mile course to San Antonio Bay. It would emerge in the Bay adjacent to the Aransas National Wildlife Refuge, home of the endangered Whooping Crane, thereby supporting their habitat as well. Voluntary dedications such as this are a cornerstone of the Work Plan developed by regional stakeholders to ensure flow in the River.

A Look at River Flow Science How much water does the River need? Well, aquatic habitats are extremely complicated, especially in a place like south Texas where there is a lot of natural variability in rainfall. Flow conditions are unpredictable and constantly changing throughout the year, and no two years are ever alike. But the native plants and animals are adapted for this. In one year, conditions may favor a particular fish species, and in another year something else. What we hope for is flow conditions that keep the river functioning naturally and in a resilient way, such that species can recover and thrive after a stretch that may not have been ideal. The flow the River needs is not a single number. It is many numbers that occur at different times, so we call it a “flow regime.” There are four components to a flow regime and each has important ecological functions:

All flow regimes have these four components in common, but the exact flow numbers needed to support a sound ecology changes along different stretches of the river. The key to determining what the numbers should be at any particular location is understanding the link between flow and habitat. This includes the habitat of both the stream itself and the riparian zone on both sides. Below is a “statistically perfect” instream flow regime for the San Antonio River at Elmendorf, as recommended by the SB2 Expert Science Team. In other words, if the scientists recommendations actually occurred, the flow in the river might look about like this. The red line is the subsistence flow, and there is also a base flow component, along with some small pulses that occur in each season, and a large pulse that we might expect every two years or so, and a flood that we might expect every about five years.

This is the actual output from the Science Team models that is reflected in the chart above:

As we take a look at each of these flow components in turn and discuss their ecological functions, we will also look at how the process of scientific evaluation was done, how the Stakeholders did their nature/people balancing act, and how all of it worked into the TCEQ rulemaking process. Subsistence Flow Starting with the red line in the chart, the subsistence flow, this is the absolute minimum flow the River can experience without incurring damage that may be permanent. We expect subsistence flows to be infrequent. This is when the River may be most at risk, but subsistence flows can have important ecological functions as well. There may be deposition of very fine particles and organic material. Non-native species that cannot tolerate very low flows and high temperatures may be killed off, which benefits the natural fish assemblage. Low flows may produce an area of restricted or isolated habitat that some species needs for reproduction. When determining a subsistence flow rate, it may be habitat availability that is the deciding factor, or a water quality factor like temperature or dissolved oxygen. For the Elmendorf location, the Expert Science Team used historical hydrology to determine that flows could be as low as 48 cfs in the summer. Meanwhile, SARA’s preliminary SB2 studies suggested that flows had to be maintained above 80 cfs or temperatures would rise so high that native fish would die. In the summer of 2011, when very low flows actually occurred, temperatures did not rise as the SB2 studies predicted. Some additional site-specific temperature modeling led the Stakeholders to conclude that 60 cfs would be an appropriate subsistence flow number. The scientists agreed, and that number was adopted in the final Instream Flow Standards approved by TCEQ. Base Flow Base Flows are the “average” conditions that we expect to see in a healthy stream. They can be variable in different seasons of the year and under different hydrologic conditions. For example, the base flow during a drought is less than during a very wet year, and winter base flows can be expected to be different from summer. For the San Antonio River, the Expert Science Team selected four seasons of three months each that correspond to the normal calendar seasons. That might seem obvious, but there are certainly places that do not have well-defined seasons, so its something that has to be evaluated and agreed on before the analysis starts. They also decided to use three levels of base flow for Dry, Normal, and Wet conditions. Based on the historical record, they defined “Dry” conditions as what occurred in the driest 25% of years, “Wet” conditions in the wettest 25% of years, and “Normal” conditions the remaining 50% of years. When each season begins, the hydrologic condition is determined by looking at how much rainfall occurred in the preceding 12 months. From an ecological perspective, base flows ensure there will be a diversity of adequate habitats to support the natural biologic community, such as deep pools, shallow riffles, and long runs. They also maintain soil moisture and the groundwater table, and provide linear connectivity along the River channel corridor. The habitat conditions are expected to vary from day to day, from season to season, and from year to year. To determine what the base flow rates should be, the Expert Science Team used models that calculated how much habitat of each type would be available under different flow conditions. SARA’s studies under the Texas Instream Flow Program involved intensive monitoring and extensive additional modeling at five locations on the River, and the results were of great use to both the Science Team and the Stakeholders. The TIFP studies produced base flow numbers that were generally higher than the models used by the Science Team, and the Stakeholders recommended the higher numbers. Because they were based on intensive science, the Science Team was ok with that. The Stakeholders retained the Science Team’s definition of seasons and hydrologic conditions. In the final rules, TCEQ did not make any changes to the Stakeholder recommendations for base flows.

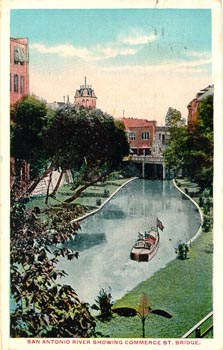

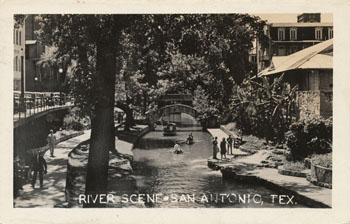

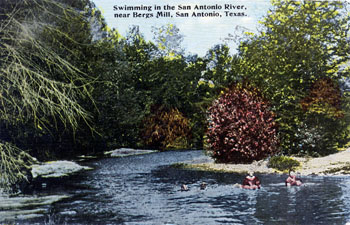

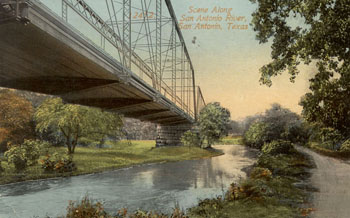

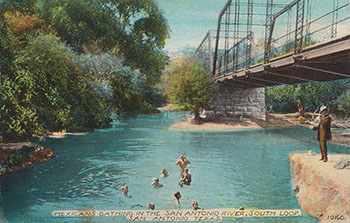

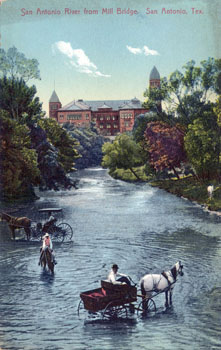

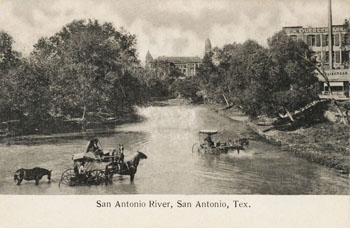

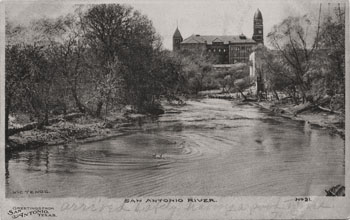

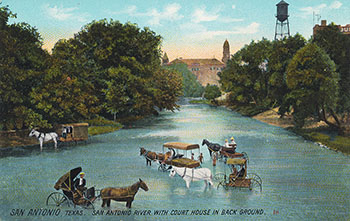

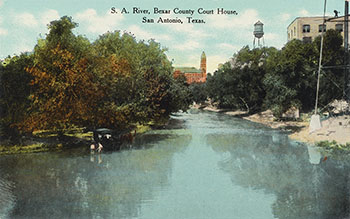

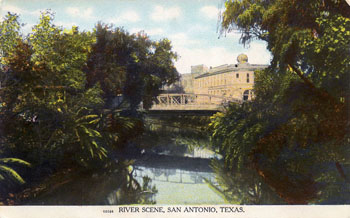

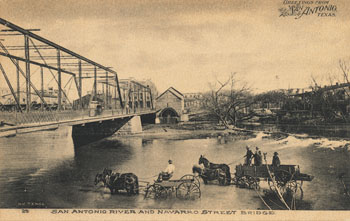

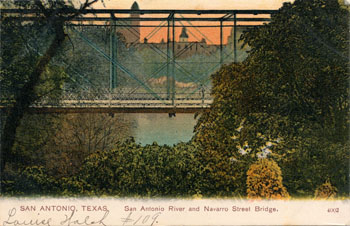

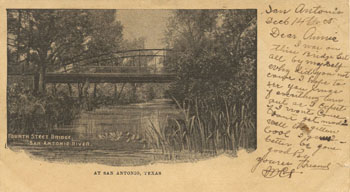

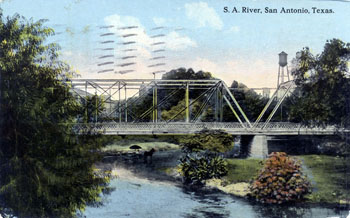

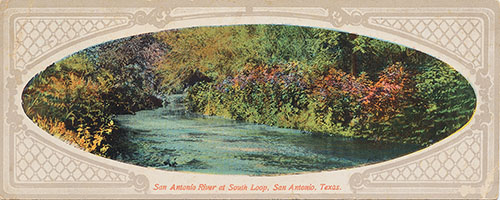

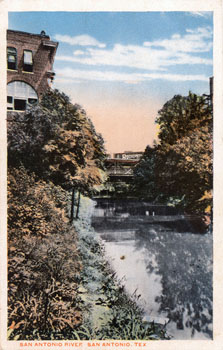

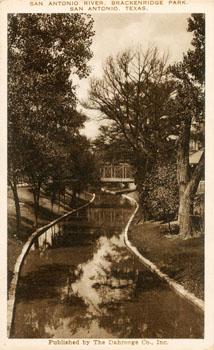

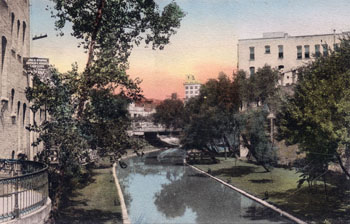

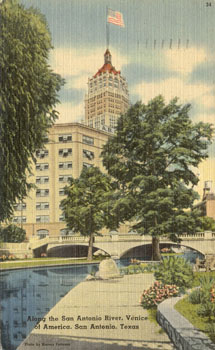

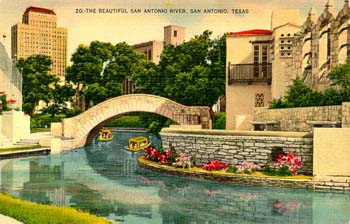

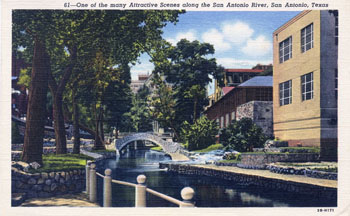

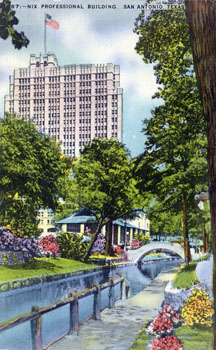

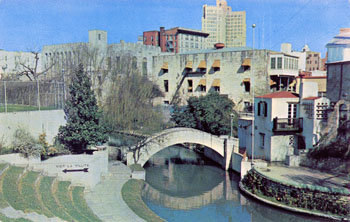

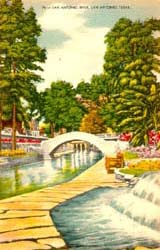

Pulse Flows Pulse flows are high flows of short duration that occur after storm events and are contained within the River channel. They have many ecological functions - they transport sediments, maintain channel features by providing scouring, disperse seeds, and provide fish with spawning cues. A pulse flow usually involves a peak flow rate, a total volume of flow that passes, and a duration. For example, the Science Team defined a once-per-season spring pulse for Elmendorf as being triggered when the flow reaches 830 cubic feet per second. The pulse ends when 6,210 acre-feet of water pass by, or when 14 days have passed, whichever comes first. The number, volume, and duration of pulse flows needed for ecological maintenance also has implications for water supplies for people. This is because in Texas, it is very unlikely that any more large in-channel reservoir projects will be built - those days are over. Nowadays the focus is on constructing smaller off-channel reservoirs and diverting pulse flows to storage. So if pulse flows are going to be passed for environmental purposes, the required number and volume and duration are important in determining when diversions to storage can be made. For example, if the River needs one pulse each spring, a diverter would have to let that one pass but it could capture a second pulse if it occurs, or it could capture high flows that might still exist after the pulse conditions have been satisfied. For the Elmendorf location, the Science Team used the historic hydrologic record to calculate two levels of pulse flows that have occurred each season, one high pulse that occurs with an expected frequency of once per year, and an even higher pulse that occurs with an expected frequency of once every two years. While the Science Team recommendations were based mostly on history, the pulse flows derived from SARA’s TIFP studies focused more on impacts in the riparian zone, sediment transport, and channel maintenance. They found that high flow pulses were only needed during certain months of the year, and they did not need to be as frequent or as large as suggested by the historical hydrology used by the Science Team, because the streamflow records used by the Science Team included large pulses caused by urban runoff which did not exist under natural conditions. The TIFP pulses are also less restrictive when it comes to diverting for water supply projects, and the Stakeholders were charged with balancing both human and environmental needs. So in the end, the Stakeholders accepted the TIFP numbers and included one extra high flow pulse recommended by the scientists. The Stakeholders also developed a Pulse Exemption Rule to apply to small diverters in cases where their diversion would not have an appreciable environmental impact. The final rules adopted by TCEQ mirrored the Stakeholder recommendations, including the Pulse Exemption Rule. Overbank Flows Overbank flows are infrequent events in which the River leaves its normal channel. In other words, they are floods. From an ecological perspective, these are crucial. They flush sediments and nutrients into the floodplain, connect the floodplain on both sides of the River, provide sediments and organic material to the bay, cause the River channel to move laterally, maintain riparian vegetation, provide life phase cues for organisms, and much more. Both the Science Team and Stakeholder recommendations included periodic overbank flows. But it is not exactly politically correct for the state to adopt rules that suggest floods ought to occur. So they did not – the overbank flow recommendations were not included in the final TCEQ approved flow standards. The San Antonio River Postcard Collection Old postcards are a valuable link to the everyday images of the past. They tell us a lot about what people enjoyed and valued, what they saw, and what they wanted to share with others. In the late 19th century and through the 1940s, sending and collecting postcards was one of America's most popular hobbies. The images of the San Antonio River below can be roughly divided into several categories: There are a handful of postcards from before 1915 that show scenes of the River below downtown. These usually feature natural pastoral scenes and bridges, which were a novelty for people accustomed to crossing in the water itself. Another small group of cards shows scenes downtown before any major improvements to the River. These also often feature bridges, and one scene of the Old Mill Crossing was by far the most popular. A few postcards were produced showing the "first" (pre-Hugman) River Walk, and about this time, postcards begin to focus much more on the "built" environment of downtown, not natural scenes. A large group of cards show scenes of the early River Walk days, and many of these picturesque scenes have remained popular until the present. Pre-1915 scenes below downtown

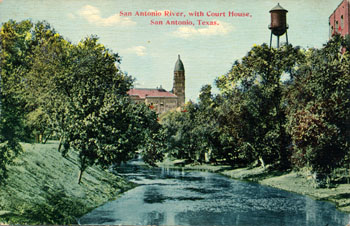

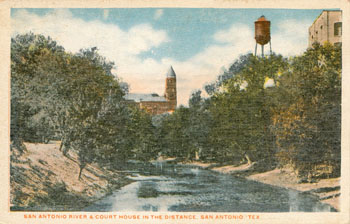

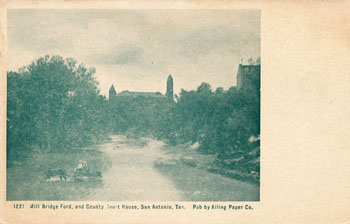

Early downtown scenes While collecting these cards I have noticed that many times when one manufacturer produced a new card, others were not to be outdone and would produce a card of almost the exact same scene. The two below are an example of this. Postcard manufacturers of the day would often add or delete things from their images. Notice the postcard on the left does not show the water tower that is in the other image. This view of the Old Mill Crossing was by far the most popular downtown scene used in postcards of the day.

On the left is yet another version of the Old Mill Crossing scene, and on the right a present-day view. It's not possible to capture exactly the same angle today - the alignment of the River channel was changed during River Walk improvements that eliminated many small curves and bends.

Postcards picturing improvements before the present day River Walk

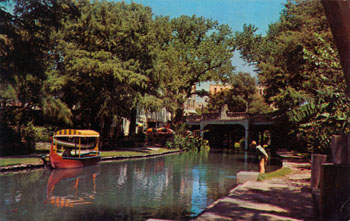

Early River Walk scenes On March 13, 1941, the Works Progress Administration formally turned over the completed River Walk to the City of San Antonio. There were 17,000 feet of new sidewalks, 31 stairways, 3 dams, 4,000 trees, shrubs, and plants, and numerous benches of stone, cement, and cedar. An estimated 50,000 people lined the River Walk on April 21 to dedicate the project and watch the first of what became an annual parade of boats.

The two cards below show how Hugman incorporated a fountain into the sidewalk, giving the feeling one is walking across stepping stones over a brook. During a later River Walk expansion, designers wanted to duplicate the feature but building codes and safety concerns forced them to make it straight and add metal grates over the openings in the sidewalk where water flows. Needless to say, the feeling is not quite the same....

Contemporary postcard views (post 1960)

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||